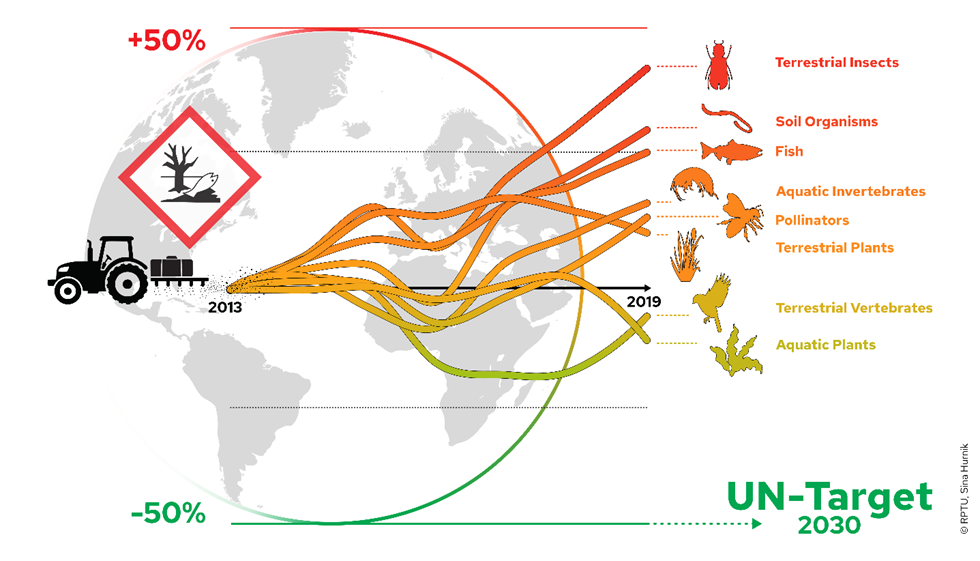

In this post, Jakob Wolfram and Ralf Schulz talk about their recent study published in Science, uncovering that the total applied toxicity of pesticides is rising, thus threatening the UN Biodiversity goal (COP15) of reducing pesticide risks globally by 50%.

You’ve probably heard of the UN’s bold 2030 biodiversity target: reduce the environmental risks from pesticide use in agriculture by 50%. It sounds like a clear, achievable goal, but a new study from us, published in Science, shows we’re not just falling short: we’re moving in the wrong direction. Our study analyzed for the first time the global status, trends and distribution of globally applied pesticide toxicities.

The Big Picture: The Total Applied Pesticides Are Getting More Toxic

Our research team, led by environmental scientists Ralf Schulz and Jakob Wolfram, developed a new tool called the total applied toxicity (TAT) – a way to measure how much environmental harm pesticides potentially cause, not just how much is used. This isn’t just about volume; it’s about what is being used and how toxic it is to the various organism groups that constitute our ecosystems.

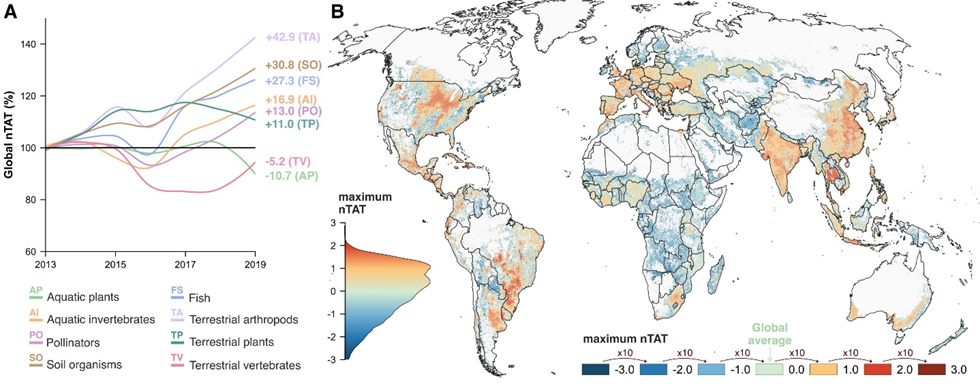

Using data from 2013 to 2019 – a period aligned with the UN’s reference timeframe – we analyzed 625 different pesticide active ingredients across seven major regulatory systems globally. We looked at how toxic each chemical is to eight key groups of organisms: fish, aquatic invertebrates, aquatic plants, pollinators, terrestrial insects, terrestrial plants, terrestrial vertebrates and soil organisms.

The result? The TAT has increased globally (Figure 1). And it’s not a small rise, for example, the TAT for terrestrial insects increased by 6.4% each year, thus by nearly 50% in only 7 years. But also for soil organisms, we found increases of over 30% in this short observation period. It’s a worrying trend driven by two main factors:

- More pesticides are being applied due to expanding farmland and intensified farming.

- The pesticides themselves are getting more toxic, especially insecticides.

Who’s Most at Risk?

The most affected groups include:

- Land-dwelling insects (like beetles)

- Soil organisms (essential for healthy ecosystems)

- Fish in freshwater systems

Even some positive trends like reduced toxicity for aquatic plants and terrestrial vertebrates (birds and small mammals) aren’t enough to offset the overall increase (Figure 1). Thus, only two groups showed slight declines, which is concerning. However, on national or continental levels, the trends were sometimes more diverse, e.g., strong increases but also decreases for aquatic plants, depending on the region. So, the scale and regulatory environment matter, and if you need more details, then look up our publication.

And here’s a key takeaway: just 20 active ingredients were responsible for most of the toxicity across animal and plant groups. That means we don’t need to ban or reduce all pesticides; quite the contrary, we can make a big difference by phasing out or replacing the most harmful ones.

Top Contributors: Brazil, China, USA, India

The study found that Brazil, China, the USA, and India were the biggest contributors to global applied toxicity (Figure 2). But don’t assume Africa is safe – Nigeria had low toxicity levels during the study period, but this could change fast as agriculture intensifies across the African continent.

Crops like fruits, vegetables, corn, soybeans, cereals, and rice accounted for about 80% of the total applied toxicity. That tells us: what we grow matters just as much as how much we spray.

The Good News? We Can Still Fix This

We found that Chile is on track to meet the 2030 target, and countries like China, Japan, and Venezuela actually saw declines in applied toxicity during the study period. That proves it’s possible to reach the UN Goals and that existing efforts of reducing pesticide risks are working to some extent.

But for most countries, including Germany, the path forward is steep. To meet the goal, these nations would need to reduce their applied toxicity to levels seen over 15 years ago. How? We think multiple approaches need to be taken:

- A shift to less toxic active ingredients

- A major push toward organic and agroecological farming

- Better data reporting and monitoring, so that science can guide this transformation

- The consumer needs to make more informed decisions

Why This Matters for You (Yes, You!)

As students and early-career researchers in ecotoxicology, this study is a wake-up call and a call to action.

- It shows how data quality and global comparability are essential for tracking environmental risks.

- It highlights the applicability of new metrics, like applied toxicity, to reveal hidden threats.

- It underlines that policy, science, and farming practices must work together to protect biodiversity.

And it’s not just about numbers – it’s about real-world impacts. Every pesticide molecule that ends up in soil or water can affect insects, fish, and the ecosystems they support. That’s the heart of ecotoxicology.

What’s Next?

The trend likely continued after 2019 – the FAO reports that global pesticide use has increased since then. Without urgent, coordinated action, only Chile is projected to meet the 2030 target.

The message is clear: We need real-time data reporting from all countries, faster policy changes, and a global shift toward safer, more sustainable agriculture.

Study Reference:

Wolfram, J., Bussen, D., Bub, S., Petschick, L. L., Herrmann, L. Z., & Schulz, R. (2026). Increasing applied pesticide toxicity trends counteract the global reduction target to safeguard biodiversity. Science. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aea8602

Technical Contact:

Ralf Schulz

RPTU University Kaiserslautern-Landau

Institute for Environmental Sciences (iES Landau)

+49 (0)6341 280-31327

r.schulz@rptu.de

Press Contact:

Kerstin Theilmann

+49 6341 280-32219

kerstin.theilmann@rptu.de

More information, including a copy of the paper, can be found in the Science press package at: https://www.eurekalert.org/press/scipak/